A Smart City to Call Our Own

Exuberant promises and sober realities clash when it comes to sensors, IoT, and Next-generation urban planning creating opportunities for safer, more responsive, and more prosperous urban communities

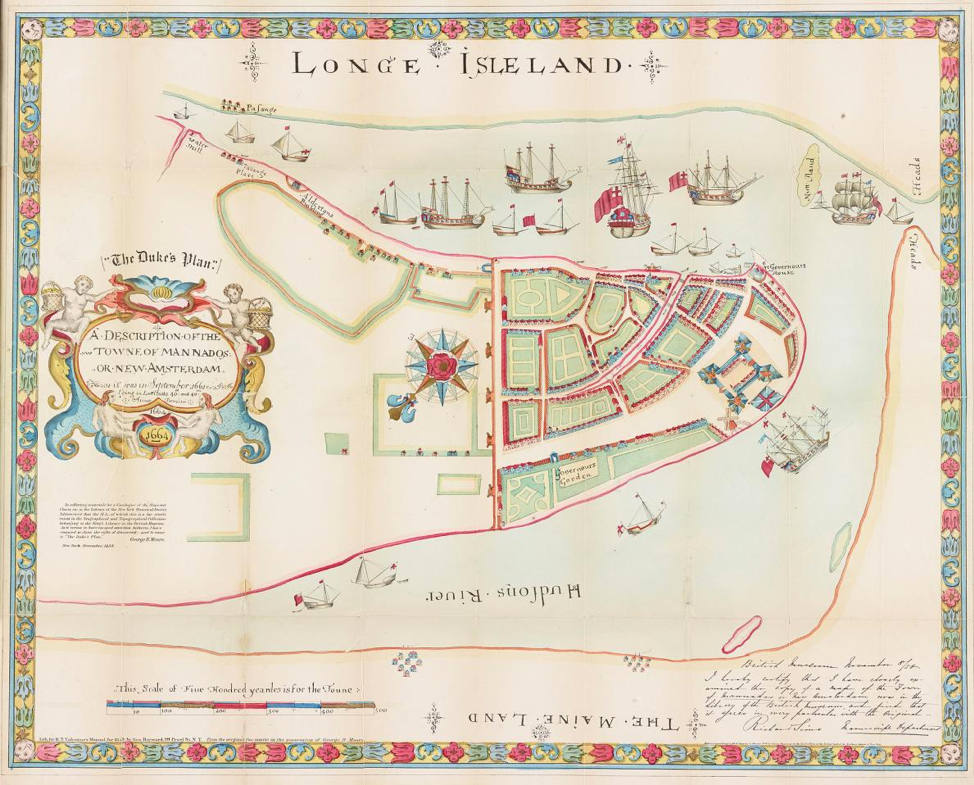

For most of history, managing a city of any size has involved reigning in the crazier effects of having a lot of humans living in close proximity while not stifling our industrious and creative impulses. When the New York City government released new documents from the founding of the city, it was clear that even in the 16th century, cities were crazy places.

City leaders needed to put restrictions on the sale of alcohol, introduce fines for fighting and for loosing sewage into the street. And they needed to monitor the behaviour of residents and even how well the new laws worked. While they reeled in behaviour, they also needed to make sure they didn’t interfere with the economic and social freedoms that had made the city such a productive and exciting place from the time of its founding by Dutch merchants.

While this balance of control and freedom has been sought by city managers for hundreds of years (if not thousands –public drunkenness was a policy problem in ancient Egypt, too), it’s only in recent times that machines could help us automatically manage the behaviour of urban populations. This is the idea of a “smart” city, one that thinks and responds on its own.

The smart city: a shining solution

Over the last ten years, “Smart City” has become an A+ public relations byword. The concept has been praised as clever and a technologically savvy way to tackle the fact that the world’s population and economic activity is becoming increasingly urban. The UN predicts that two-thirds of us will live in cities by the year 2030.

This technological approach has been made possible by increasingly ubiquitous internet connectivity and the miniaturization of almost every kind of electronics, from CPUs to storage to sensors. Cameras watch almost every London or Beijing street corner and cover thousands of roads for traffic monitoring and law enforcement. Devices like radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags are now in our passports, pallets, and purses – objects that typically aren’t networked. This technology can provide inexpensive, wireless, battery-free connectivity and interactivity for all kinds of objects. Every day, millions of people use RFID systems without even knowing it: passes, badges for motorway tolls or access to workspaces, passports, electronic car keys, and cargo tracking. In San Diego, the city installed smart streetlights to spot parking spaces, listen for gunshots, and track air pollution. In San Francisco, the city is experimenting with variable rates at parking meters to encourage different kinds of behaviour.

There is a range of definitions of a smart city, but the business consensus is that smart cities utilize IoT sensors, actuators, and technology to connect components across the city. This connects every layer of a city, from the air to the street to the underground. It’s when you can derive data from everything that is connected and utilize it to improve the lives of citizens and improve communication between citizens and the government of that city.

Defining the Smart City

IBM: “…synchronizes and analyzes efforts among sectors and agencies as they happen, giving decision makers consolidated information that helps them anticipate problems [and] manage growth and development in a sustainable way that minimizes disruptions and helps increase prosperity for everyone.”

Siemens: “Several decades from now cities will have countless autonomous, intelligently functioning IT systems that will have perfect knowledge of users’ habits and energy consumption, and provide optimum service. The goal of such a city is to optimally regulate and control resources by means of autonomous IT systems.”

Cisco: “…the seamless integration of public and private services, delivered across a common network infrastructure, to individuals, governments and businesses.”

Many of today’s smart cities implementations are being driven by global technology companies that offer these kinds of solutions to cities, such as IBM, Cisco, Siemens, Microsoft, Hitachi, and Huawei. These companies envision the smart city as an enormous machine, a vision that Adam Greenfield at LSE Cities says “appears to have originated within these businesses, rather than with any party, group or individual recognized for their contributions to the theory or practice of urban planning.” The corporate smart-city rhetoric, he pointed out, was all about efficiency, optimization, predictability, convenience, and security. “You’ll be able to get to work on time; there’ll be a seamless shopping experience, safety through cameras, et cetera.” Smart cities could help people avoid traffic jams, find a parking spot, report a pothole, or have an overflowing dumpster picked up. Better living through biochemistry gives way to a dream of better living through data. You can even take an MSc in Smart Cities at University College, London.

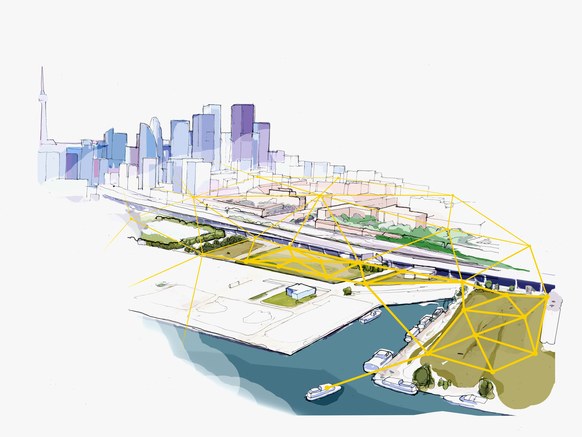

In Toronto, Google’s parent company Alphabet, is trying to build the most techno-optimist vision of the concept, a waterfront community development that will monitor its residents’ movements to test new ideas about waste management, affordable housing, even outdoor furniture. But that experiment lives in the future. Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs, which is spearheading the Toronto effort, says it will spend all of this year collecting input from residents about what they’d like to see in their neighbourhoods.

Sidewalk Labs promises to embed sensors everywhere, collecting streams of data about car and pedestrian traffic, noise, air quality, energy usage, and waste. Cameras may even help the company nail down some of the completely intangible: Do people enjoy this green space? Or this art installation? Do residents actually use this popup clinic for flu shots? Which is the best corner for a market? Are pedestrians local, or from a different neighborhood? Or city?

The smart city: a murky problem

Not everyone is as excited about the smart city. The term “smart city” has also been accused of being a mostly empty phrase that seems to mean “places that collect data about stuff.” In the 1930s, urbanists like the American, Lewis Mumford and architects like Sigfried Giedion worried about machines and materials in relation to urban design. Mumford was wary of building cities around cars, and in the 1960s urbanist Jane Jacobs agreed with the idea that cars “killed” the traditional American city.

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

― Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Others are even more critical. The Guardian ran an opinion piece on how smart cities might be a threat to democracy. Some of the critique revolves around the threats and consequences of constant, invisible surveillance. One of the first people that thought about this concept was Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher and social theorist who spent years designing what he called the “Panopticon.” He imagined an institutional building, perhaps a prison, that would also serve as a means of controlling people. The idea was that all of the occupants could be observed by a single person, without them being able to tell whether or not they were being watched. According to Bentham the fact that the inmates wouldn’t know when they were being watched would mean they would act as if they were being watched at all times, and would feel compelled to manage their behaviour accordingly.

Intentional or not, this sounds very similar to the capability of a smart city. Bentham, a strong proponent of this approach, probably agrees with the critics more than the smart city proponents.

He described the Panopticon as “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example”. In another letter, he described the Panopticon as “a mill for grinding rogues honest.”

Michel Foucault, the French theorist, agreed with Bentham about the power of his invention:

The Panopticon is an ideal architectural figure of modern disciplinary power. The Panopticon creates a consciousness of permanent visibility as a form of power, where no bars, chains, and heavy locks are necessary for domination any more.

Could be a little aggressive. Is there a way to have the best of both worlds?

Lesson: Throw a Party that You Would Like to Attend

So far, the best cities have all been the result of an organic development over time, not a grand plan or vision. The smartest, most connected cities – London, Barcelona, Shanghai, New York, and San Francisco, all have had a rich and vibrant culture before they became smarter cities. On the other side, cities like Brasilia, Masdar, Songdo, and Norilsk all stand as testaments to what happens when you try to plan an entire city – people either don’t move there, or they are miserable when they do.

Early indications show that while building “smart cities” might be difficult and even undesirable, making cities “smarter” in specific ways is definitely worthwhile. Traffic, one of the biggest negatives of living in a big and thriving city, is a great example. One of the major goals of developing countries is to build smarter cities to avoid different kinds of congestion, accidents and delays. One solution is Intelligent Traffic Management, which is a combination of sensors, imaging, messaging, logic, and communication that work independently, and together. Another solution involves traffic monitoring for security and access reasons, scanning and recognizing licence plates to protect urban areas or finding stolen vehicles with the help of IoT-Driven Automated Object Detection Algorithm for Urban Surveillance. A city can “think” to solve a very specific problem.

This is the most likely path for “smart city” development: making the naturally improvised reality of city living easier and more productive while preserving the environmental factors that brought people there in the first place. The Internet of Things and information and communication technologies are still in their infancy as they are being applied to real-world problems. While the initial solutions may focus on transportation and security, we can see that even the most promising cities will be a source of problems as well as solutions.

Discovering Cities: Lidar Past, Present & Future

Discovering Cities: Lidar Past, Present & Future  “The World Isn’t Flat, It’s Panoramic”

“The World Isn’t Flat, It’s Panoramic”