Little guys in a real big prairie: how thermal imaging is helping rescue a once-vanished species

Researchers are using infrared technology and artificial intelligence to help track the elusive black-footed ferret in an effort to save them.

The Northern Great Plains span five U.S. states and two Canadian provinces, encompassing more than 180 million acres. Covered by prairie grass and farm fields, blown by high winds, this vast expanse is still home to the tiny, elusive members of a species once thought extinct: the black-footed ferret.

The species declined throughout the 20th century as a result of habitat loss, human-introduced diseases, and indirect poisoning from prairie dog control measures. Black-footed ferrets were declared extinct in 1979, but a residual wild population was discovered in Meeteetse, Wyoming in 1981. A captive-breeding program launched by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service resulted in its reintroduction into eight western US states, Canada, and Mexico from 1991 to 2009.

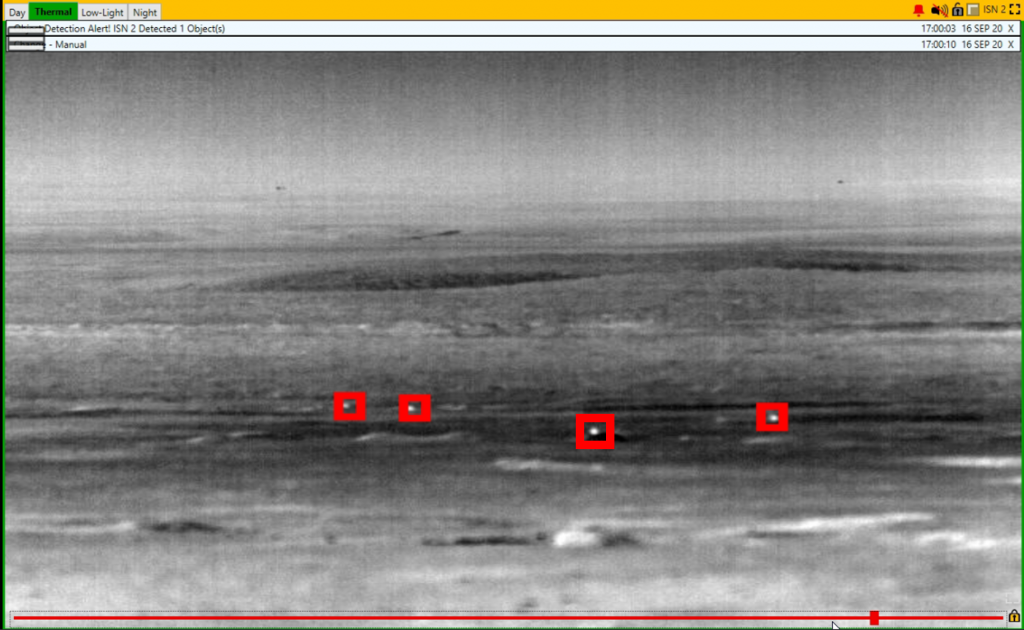

Infrared imaging of black-footed ferrets

While finding solutions is a challenge, actually finding the ferrets themselves may be an even bigger one. Black-footed ferrets are small (less than two feet long), fast, well-camouflaged, and are active above-ground only from dusk to mid-morning. To effectively design conservation interventions—and reach the recovery goal of 3,000 adults in the wild—experts need to estimate the size and health of existing wild populations.

As part of WWF’s Northern Great Plains Program, Black-footed Ferret Restoration Manager Kristy Bly has been working with her team to incorporate infrared FLIR cameras in detecting and monitoring these elusive animals. The ability to monitor ferret populations is crucial for the protection of this recently reintroduced species, with fewer than 300 black-footed ferrets currently living in the wild. Through population monitoring and disease control, WWF and their ferret recovery program partners hope to restore the population on the Northern Great Plains, with a goal of having 3,000 adult ferrets thriving in the wild.

Typically, researchers use high-intensity spotlights mounted to trucks to search for ferrets, looking for their tell-tale emerald green eyeshine. While effective, this technique relies heavily on field capacity and unobstructed views—and observers must move constantly to bring new areas into view. In addition, ferrets are likely scared away by the light and truck sounds, further inhibiting our ability to estimate population numbers.

To address this challenge WWF, USFWS, and FWD – in partnership with FLIR Systems and with funding from the SBB Research Group – tested various forward-looking infrared (FLIR) cameras to locate ferrets on the Fort Belknap Reservation during 2019-2020. FLIR cameras use a thermal system that senses infrared radiation from an individual’s body heat.

The researchers’ goal was to determine how effectively four FLIR camera models (FC-608O, Vue Pro, Scout, and Tau 2) could located ferrets at night, distinguishing them ferrets from other animals, and estimate the number of ferret kits in each litter.

FLIR FC-608O |

FLIR Vue Pro |

|---|---|

|

|

They found that the Tau 2 with a 100 mm lens was the most useful of the four cameras. The Tau is a high-performance long-wave infrared (LWIR) camera, designed to detect small, hard-to-find targets over long distances. Its image processing capabilities provide clearer thermal details in challenging environments, but the researchers found discrepancies between the focus and clarity of the FLIR camera and the monitor-produced images. While the camera images were clear, on the monitor they appeared fuzzy, requiring moving closer to the target for clearer images.

Once solution was to incorporate artificial intelligence to automatically detect ferrets and notify researchers to their locations. The WWF partnered with Gantz-Mountain to test their MT-5-R Long Range Intelligence Sensor Node system, which boasts a FLIR Boson 640 LWIR camera, artificial intelligence capabilities, an onboard radio, intelligent sensor nodes, and is capable of transmits clear images of the target to a monitor.

The system effectively identified and tracked ferret-sized animals from 500 meters away, often before they were visible in the spotlight. This automation made it easier for WWF and partners to locate ferrets living on the Reservation.

Measuring progress toward recovery of this rare species relies on estimates of their numbers in the wild. FLIR’s thermal imaging infrared cameras combined with Gantz-Mountain’s smart-edge surveillance systems are a promising black-footed ferret detection tool – one that WWF and partners will continue testing.

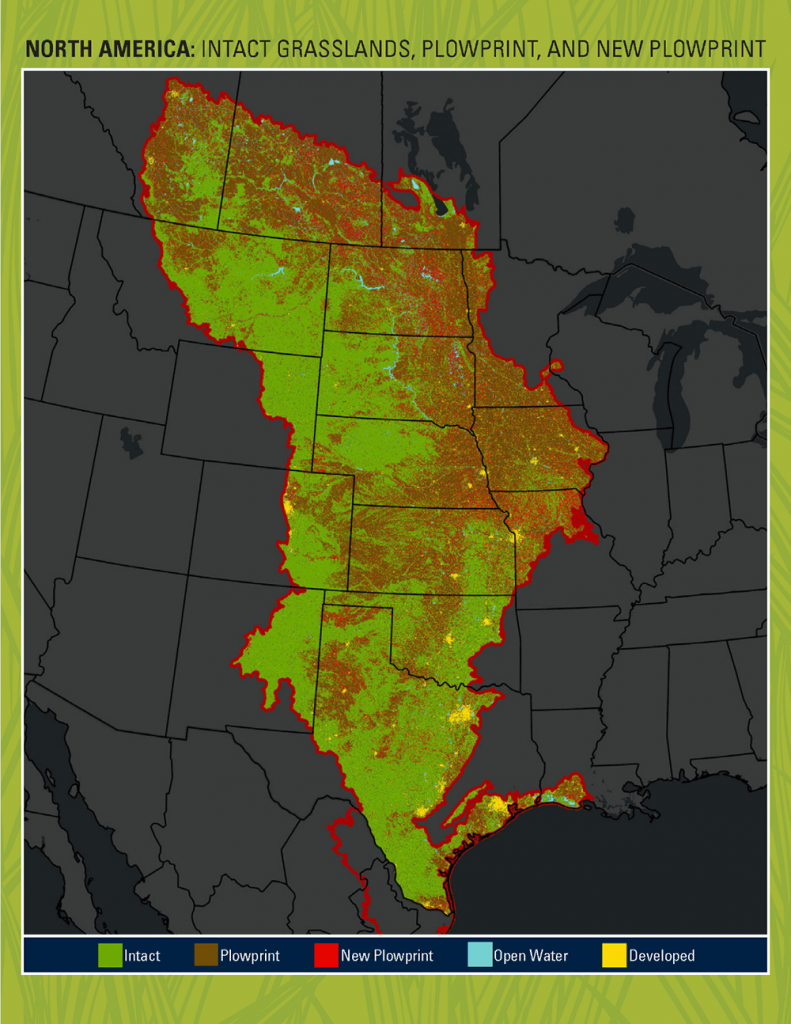

Vanishing Habitat

While multiple organizations are working to rescue the black-footed ferrets, an important predator for regulating prairie dog populations and the overall health of the prairie grasslands, pressure on the total ecosystem continues to mount. According to the WWF, nearly 1.8 million acres of grasslands were destroyed across the US and Canadian Great Plains in 2020. Since 2016, a total of almost 10 million acres have been plowed across the region, which is an area nearly as large as New Jersey, Connecticut, and Rhode Island combined.

This analysis is based on the USDA’s Cropland Data Layer, the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Annual Crop Inventory, and Sentinel-2 satellite data classified using Google Earth’s Engine. The Sentinel missions carry a range of imaging technologies, such as radar and multi-spectral VNIR-SWIR imaging instruments built by Teledyne for land, ocean and atmospheric monitoring.

At the same time, the prairies have been emptying of people. The rural Plains have lost a third of their population since 1920. Several hundred thousand square miles of the Great Plains have fewer than 6 inhabitants per square mile (2.3 inhabitants per square kilometer). There are more than 6,000 ghost towns in Kansas alone, according to Kansas historian Daniel Fitzgerald. This continuing population loss has led some to suggest that the current use of the drier parts of the Great Plains is not sustainable, and there has been a proposal to return approximately 139,000 sq mi (360,000 km2) of these drier parts to native prairie land efforts such as Buffalo Commons.

Imaging the prairies at both levels, from the tiny ferret to thousands of square miles of landscape, will help us adapt to whatever the future holds.

As Martha Kauffman, VP of WWF’s Northern Great Plains Program, explains, “We rely on grasslands for pollinators, clean water, and healthy air. When grassland habitats are plowed up, it puts all of us in jeopardy. But with the right policies, incentives, stewardship, and increased efficiencies, we can stop the destruction and even expand native grasslands, ensuring that they’ll be around for generations to come.”

Update: Teledyne FLIR has once again partnered with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in its mission to protect vulnerable wildlife and restore struggling habitats. The organizations met in central Montana at the Fort Belknap Reservation to track black-footed ferrets, one of North America’s most endangered mammals. The goal was to test infrared camera solutions, both as a fixed-mount camera and as a drone payload, to determine if the technology could provide a faster, more accurate method of spotting the elusive ferrets.