Recapturing the cinematic magic of film

How digital tools and techniques are keeping the soul in cinema

Every film is an illusion — the rapid projection of 24 still images per second creates a sense of motion so real that the original filmgoers would run and hide from the first screenings, or so legend has it. Making movies has always been both a technical and creative exercise, but the result remains a kind of magic.

The beginning of the end?

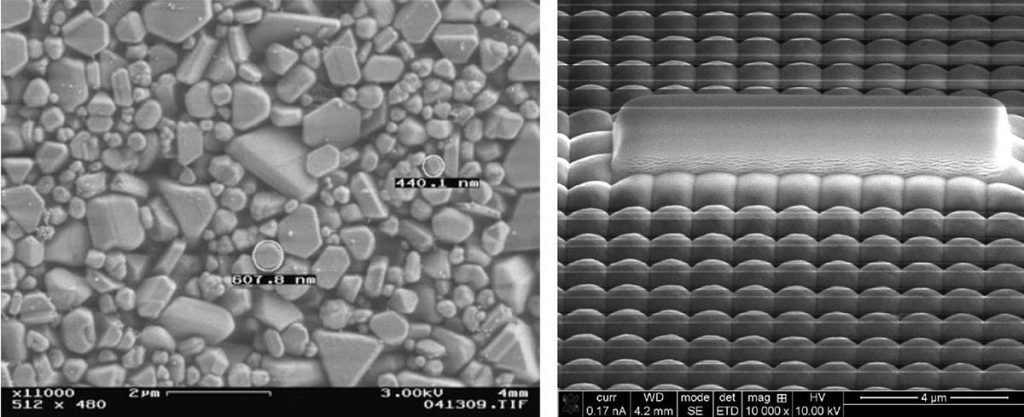

A century later, when Lars von Trier’s The Idiots and Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration became the first features shot entirely on digital video, film purists began to worry that this new technology would change cinema. To analog advocates like Christopher Nolan, Daniel Day Lewis, and Quentin Tarantino (whose Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was captured on a variety of film stock in 2019), accidents and organic imperfections are built into what film and movies made with them “should” look like. The characteristic grain of analog (as opposed to digital) film, which results from the random formation of microparticles in the developing fluid.

These directors see digital filmmaking as a death knell for the medium, a situation that has only worsened as analog film’s decline has made it a niche medium for feature films. Only 24 films were shot on 35mm in 2018, even as its aesthetics continue to inform modern film, and few cities outside the biggest metropolises have theatres that still use 35mm projectors.

The numbers tell one story, but the question remains: can digital cameras capture the true magic of cinema? That may have been debatable a decade ago, but today the answer is clear: the power and versatility of digital cinematography means that it can produce results virtually indistinguishable from analog film. In fact, with its greater low-light performance and dynamic range, today’s high-end digital technology can go even further, doing things that film never could.

Moving on while looking back.

In Tarantino’s 2012 Antebellum revenge movie, Django Unchained, there’s an infamous moment when Leonardo DiCaprio, playing the movie’s villain, slams his hand into a table, then raises it back up covered in blood. It’s an unsettling beat for two reasons: the menace of the threat he’s underlining, and the fact that the blood is real, the result of DiCaprio having cut his hand on a piece of shattered glass.

It’s a perfect example of the blurring of fiction and reality that can make movies so compelling, but it also illustrates that the heart of cinema lies in what the camera captures, not in what format it records it on. You can have all the precision imaging equipment in the world, but as cinematographer Roger Deakins puts it when describing his own digital workflow, the quality of a film is “not about the bloody technology, it’s about the person behind it.”

Besides, even most die-hard analog filmmakers still include digital processes in their pipelines. In his essay “On Color Science For Filmmakers,” cinematographer Steve Yedlin points out that negatives need to be processed into reels and then reproduced for distribution. That means no moviegoer ever actually sees unaltered film. Instead, Yedlin proposes that filmmakers identify the particular elements they enjoy about analog film, find the data they’ll need to measure for them, and use the flexibility of digital to recreate that feel.

In his essay, Yedlin argued that “The elusive thing that we call the photographic look is an abstract phenomenon. It’s the aggregate perceptual experience that emerges from the sum of many smaller attributes that clue the eye.” He splits the attributes of “the photographic look” into three broad categories: intrapixel (contrast, density, color), spatial (resolution, sharpness, halation), and temporal (motion blur, exposure, frame rate, rolling shutter). The point is, that if you watch his proof of concept, “Display Prep Demo,” all of these factors can be accommodated (simulated) with an all-digital process.

Lights, meet camera.

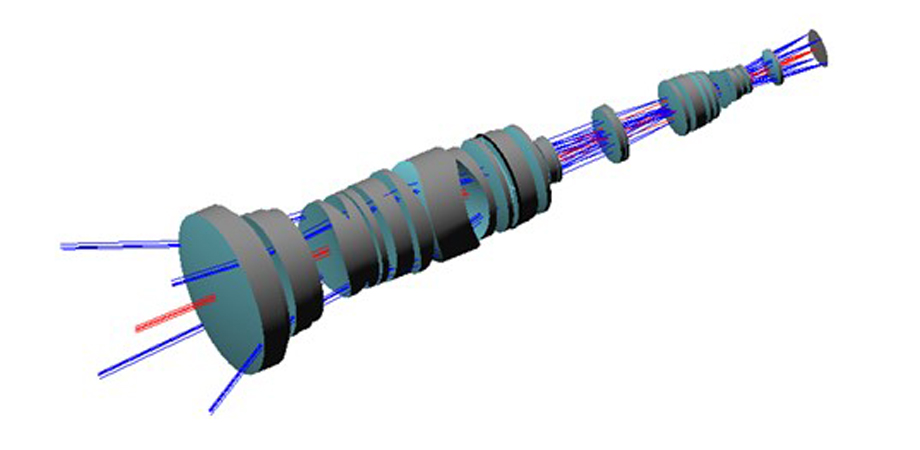

Like film production itself, lenses consist of multiple parts working together (an anamorphic zoom lens can house 30 lens elements). When combined in just the right way, these elements bend and re-bend the light entering the lens, focusing it onto the camera’s sensor. New technology like light field cameras could hypothetically replace standard cameras someday, using multiple sensors to record the intensity and direction of incoming light like lidar capturing 3D spaces, but so far, no commercially viable models have been produced. And so, cinematographers continue to use lenses, often altered for effect, like the diffuser filters used to dull the images in the Western film, Old Henry.

As complex as it may be, a camera’s main function is simple: it records light. Cinephiles may not want to reduce Peter O’Toole’s performance in Lawrence of Arabia to a simple measure of luminosity, but that’s exactly what a modern RED DSMC2 would do, 35,389,440 pixels at a time. The resulting histogram shows the distribution of light across every one of these pixels — the total dynamic range of the sensor.

That may sound clinical, but what it means is that instead of experimenting with film stocks to arrive at the right look, cinematographers like Yedlin can use LookUp tables (LUTs) in the camera’s settings to change the input values of colors, saturation, brightness and contrast, as he did on the set of Knives Out. Today’s digital cameras can record a wider range of information than film ever could, whether that’s low-light performance, increased dynamic range, or even resolution, giving cinematographers even more control over the image they capture.

Let the processing begin.

Once light and sound have been recorded, the film’s post-production process has all the materials it’s going to get from production — at least until the inevitable reshoots. Post-production, then, is a diverse set of activities, from color correction to editing to ADR (automated dialogue replacement).

It’s here that an editor does much of the work that defines the “look” of the film, altering color balance and contrast. Provided the camera has captured all the “information” the cinematographer set out to capture, a modern set of editing tools provides enormous latitude in transformation.

To create the much-romanticized texture of film grain, for example, the difference between using an algorithm to generate grain, rather than the rasterized images of grain from existing reels. On the one hand, images from film reels may have “authentic” grain, but algorithmic randomness is in other ways truer to the microparticles randomly form in processing solution. And these “random” effects can continue to be improved over time with machine learning until they’re indistinguishable from the real thing.

Shaping the light with imperfections

Ian Neil, award-winning cinematographer and SPIE fellow described the desire to make the digital cinema image look more organic. The lower cost and greater versatility of the digital camera makes it the go-to choice, but even without elaborate processing, the camera lens can make a huge difference, expanding interest in older vintage lenses as well as new designs that are created to give an imperfect filmic look.

In fact, this de-tuning of the image has a long history. In Barry Lyndon, the cinematographer used filters and other methods to make the typically very contrasty 1970s-era film look softer, to better match the painterly approach that the director was looking for. Other techniques could increase light reflection or reduce clarity, including physically scratching the lenses, covering them in gauze or even Vaseline, or even rearranging the optics inside the lens. Many of these ‘hacks’ had to do with achieving a specific look that told the story best, or was simply popular at the time. Since the beginning of film, trends have been a powerful motivator.

If you do the same thing, you get the same old thing.

Using film is the surest way to produce filmic results, and filmmakers and their financial backers are always looking for certainty. It’s no coincidence that every year another or tech startup promises the formula for box-office success. But analogue techniques can’t guarantee a hit. The soul of cinema isn’t made of celluloid.

When John Rambo dives into a tree to escape a helicopter in First Blood, the cry of pain is real: Sylvester Stallone broke his arm performing the stunt. The iconic beat in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Indiana Jones shoots a scimitar-wielding opponent in an anticlimactic shrug only happens because Harrison Ford was exhausted and ill.

The spontaneity that brings cinema to life doesn’t disappear when movies switch to digital. If anything, new tools and technologies are making it easier than ever for filmmakers to focus on what truly matters: showing audiences something magical.

No Excuse Cinematography with Joe Cicio

No Excuse Cinematography with Joe Cicio  Keeping up with CMOS Sensor Design

Keeping up with CMOS Sensor Design