Student’s New Anti-Poaching Solution Unites Thermal Imaging and Artificial Intelligence

A clever combination of low-cost FLIR ONE Pro cameras offers promise in tackling a global challenge

Thousands of endangered animals are illegally hunted every year in Africa. Often, rangers get caught in the crossfire trying to protect them. Current prevention methods include rangers stationed acting as guards or monitoring camera feeds; unfortunately, this can be prone to human error and can be tedious for those standing watch. Some parks rely on advanced thermal security cameras to protect the tiny-but-growing population of African rhinos, provided through a joint-project by the World Wildlife Fund and Teledyne FLIR.

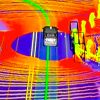

For elephants, also endangered, but with a larger population spread across a much greater geographic area, there are different challenges, and different economics for successful solution. An effective low-cost thermal solution could have a huge impact on rangers’ ability to stop poachers. It’s a problem Anika Puri, a 17-year-old from Chappaqua, New York, hopes to address with ElSa (short for “Elephant Savior”), is a real-time poacher detection solution that uses artificial intelligence to analyze infrared videos taken by a drone-mounted FLIR ONE camera.

Motivated by a shocked recognition of the still-thriving trade in ivory, Puri has been working over the last few years on a solution to help protect elephants. The MIT freshman has already made impressive strides in the world of STEM. She won the 2022 Peggy Scripps Award for Science Communication at the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair, where 1,800 students competed in a range of categories. Her presentation to research experts on her anti-poaching program, which won her a top award in the competition’s earth and environmental sciences category.

Similar drone-based AI solutions are currently used in some parks but have two disadvantages: low accuracy and high cost—as much as $10,000 per drone. ElSa, on the other hand brings significant improvement over current methods with 91% accuracy rate through the AI alone and only costs around $300. The major cost savings come from the fact that ElSa runs off a simple iPhone 6 receiving thermal video from a FLIR ONE thermal camera attached directly to the phone. With the phone mounted to a drone, ElSa captures aerial footage which it then analyzes in real-time.

Over two years, Puri created her low-cost prototype of a machine-learning-driven software that analyzes movement patterns in thermal infrared videos of humans and elephants. Puri says the software is four times more accurate than existing state-of-the-art detection methods. It also eliminates the need for expensive high-resolution thermal cameras, which can cost in the thousands, she says. ElSa uses a FLIR ONE Pro thermal camera with 206×156 pixel resolution that plugs into an off-the-shelf iPhone 6. The camera and iPhone are then attached to a drone, and the system produces real-time inferences as it flies over parks as to whether objects below are human or elephant.

An advantage of Puri’s AI over systems currently in use is how the technology identifies people and animals on the ground. Current AI systems analyze shapes in the scene to distinguish targets and thus require a certain degree of resolution in their images to maintain accuracy. ElSa works by analyzing the movement pattern of its targets and can achieve accuracy with far fewer pixels, meaning the camera can be lower resolution or further away.

Using data collected from Kruger National Park in South Africa, Puri trained ElSa to recognize factors such as movement speed and how the target turns as a way to differentiate between humans and elephants; these are also what allow the program to operate with fewer pixels than current methods. The AI can identify non-moving objects like bushes or trees and then uses those as anchor points to track moving objects. ElSa uses these anchors as references for object speed and direction and allow the system to maintain tracking despite the drone itself being in motion.

Smarter solutions for even tougher challenges in the future

Successful anti-poaching and habitat management approaches have been shown to help endangered wildlife populations start to recover. But more elephants means more tracking, which can cover an enormous geographic area. Elephants roam great distances, migrating in search of food and water sometimes as much as 300 miles in a year, as far as 35 miles in a day. In the future, food and water will continue be a problem in Africa, with droughts in 2022 leading to many deaths and driving animals further and further. With more successes and greater risks, cost-effective and easy-to-use technological solutions may make all the difference.

Avoiding bumps on the road: how thermal imaging can improve the safety of autonomous vehicles

Avoiding bumps on the road: how thermal imaging can improve the safety of autonomous vehicles  Little guys in a real big prairie: how thermal imaging is helping rescue a once-vanished species

Little guys in a real big prairie: how thermal imaging is helping rescue a once-vanished species